Early this year I was reviewing the recent Ships of the Line calendars and stumbled upon an absolutely superb rendering of the fan-made Phalanx-class, which has appeared in the calendar multiple times under a variety of different starship names. I encourage you to look it up if you aren’t familiar with the ship.

Professionally, I have an extensive background in post-production in both TV and film projects. Photoshop, After Effects, 3DS Max and Maya are my daily bread and butter, and in spite of having more model starships than is reasonable, and having a great love of technical drawings, maps, and diagrams, I had never actually tried making one of Star Trek’s famous “Okudagram” Master Systems Displays.

Mostly, I suspect this was just due to a total lack of time and commitment.

I’ve modified existing MSDs in the past – sometimes quite extensively – but there came a point where I simply had enough. If I really wanted to have my own ship rendered in the way that I wanted, I was just going to have to do it myself.

The Archon-class

The Archon is Star Trek Online’s successor to the Sovereign-class lineage. Designed and built by Ian “JamJamz” Richards of Cryptic Studios, the ship has a bit of a cult following in some of the game’s community circles, but she’s not without controversy owing to those overly ‘ample nacelles’ that adorn her pylons. Simply put: they are absolutely massive, and many Star Trek Online players spend a lot of time finding combinations of parts to give the ship a reduction mammaplasty. Still, she’s unique and – through virtue of her more obscure status in the wider Star Trek fandom – she has never been explored before.

So what makes the ship special?

Traditionally, Star Trek Online releases new ships based on old classics that are designed to explore aspects of canonical abilities seen by ‘hero’ ships in the shows and movies. The examples are easy to find: If you get a retrofit Intrepid-class, you’ll find it has an ability to use the ablative armour systems seen in Voyager’s finale, End Game. Or, if you get the new spin-off of the Defiant-class (the ‘Valiant’, named after the ill-fated cadet-crewed ship of the same name in Deep Space Nine) you’ll get an ability to fire off barrages of quantum torpedoes; those torpedoes being something that the Defiant was known for during its run on TV.

So how do you define a Sovereign? The Archon is not the first refit of the Sovereign design that we’ve seen. The preceding Regent-class gave it a set of metreon gas launchers that can be ignited to produce ‘The Riker Maneuver’ from Insurrection. The WizKids-exclusive Vizier class variant took this a step further and gave the ship a metreon gas torpedo launcher. So what did they give to the Archon?

A phase cloaking device.

…Wait, what?

Putting my shamelessly technobabbling head into gear, I’ve spent a huge amount of time talking to fellow guild mates exactly why the heck you’d put a phase cloaking device on a ship that was most famous for simply beating the ever-loving hell out of Borg, Son’a, and Remans, and looking fabulous while doing so.

The logical if cynical answer of course, is that Cryptic studios likes to make money, and throwing a very popular cloaking device onto what could be* the most popular class of ship in Star Trek is a bit of a no-brainer.

But I think we can do better. I think the Archon has a dark origin. She was released not long after the conclusion of Cryptic’s Iconian War campaign – a devastating war that saw Starfleet gutted and – by word of one of the game’s developers – so badly depleted that every single member of it’s flagship class of starships (the Odyssey) were either crippled or destroyed. Earth itself came to within minutes of being glassed by an Iconian fleet, and was spared at the last possible moment by an improbable (though some may argue inevitable) moment of Starfleet time travel tomfoolery. All this, after an extraordinary number of vessels were wasted in trying to smash through the walls of the Iconian Dyson sphere in an earlier mission led by a hard-headed Klingon.

…Maybe, just maybe, Starfleet needed something a little bit more drastic. To have been launched so soon after the conflict ended, it seems likely that the Archon class was already in development during the course of the Iconian War. My head canon for the Archon class is that it shall forever be the last-resort Starfleet weapon that never got to fire its guns in anger during the war for which it was designed. Can you think of a better way of getting into a heavily-fortified Dyson sphere than a phase-cloaking device that lets you pass through solid matter? I can’t. And so this is where my theory begins. The other big clue is the fact the ship has curiously-chosen Intelligence-specced seating, implying activities that fall outside the usual loud-and-proud pomp and circumstance of Starfleet fanfare.

Oh yes, the Archon is a dark horse of a ship indeed, and I really wanted to reflect all of this in her Master Systems Display. Here she is…

The MSD’s basic colour profile is broken down into four simple divisions. Crew areas and other operational equipment is rendered in Pantone 7675 C (violet) while engineering systems are rendered in gold Pantone 728 C. Tactical systems (including phaser banks and torpedo launchers) are rendered in red Panton 172 C, while finally, warp plasma related systems are rendered in a light blue Pantone 2975 C. This palette is maintained across the entire systems diagram.

There are some challenging aspects of the Archon in how she is laid out. An examination of the model in detail (which had to be done before this project) revealed a likely warp core ejection point that was a very long way forward of the one found on the Sovereign-class. What’s more, the Archon has a very large deflector dish which is just a short way forward of that position. Main engineering and the deflector space were probably going to be in very close proximity to one another, which left the question of just how much space could be allotted to the main shuttle bay in the spaces above. While the Archon wouldn’t be the first starship to put a warp core so close to the deflector (the Constitution’s core ran vertically through the ship’s neck, directly behind the deflector dish), it could be the first starship in over a hundred years to do so. Design wise, it made more sense to find ways to fit the two around each other rather than completely reinventing the concept of the deflector as we’ve known it since TNG.

In short: the Archon’s critical systems are all bundled up into a space that’s quite confined. So long as someone is reasonably good at Tetris, then this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Traditionally, capital ships could concentrate their key systems in one area, and focus their armour schemes around a single, smaller area of the ship (called a ‘citadel’) for more weight-efficient defence. Notably, this area on the Archon is visibly defined by a grey boundary line that runs up the side of the ship from its ventral hull, to a point as high as the saucer section. It’s plausible (from the perspective of someone trying to make an MSD for this ship) that this area marks the most heavily armoured section of the secondary hull, with thick concentrations of ablative plating and structural reinforcements. This latter point would seemingly be supported by just how wide the secondary hull becomes at those frames.

If that is the case – and I did assume it to be so – then the majority of critical machinery would need to be drawn within that zone.

This quickly brings about a second point of note: the Archon’s bridge is set a very long way aft compared to other classes of vessels. The only other ship that I can think of that has a bridge that far aft on the saucer is the Intrepid class, but she’s a much smaller type. The bottom line is that if I was to be faithful to other ‘large’ ships (particularly the Sovereign) which place a large ODN shaft underneath the bridge to carry the computer network cabling, then some thought would need to be given to the position of other large components including the computer cores themselves. And that’s before I’d even thought about turbolift shafts.

Saucer separation:

A feature of note on the Sovereign-class is the existence of saucer separation. When John Eaves designed the ship back in 1995-1996 ahead of its first appearance in First Contact, he drafted plans that included this capability, and it was never used on screen. This leaves its status in canon as uncertain, but all the same the concept has persisted and numerous drawings of the ship can be found that preserve the saucer separation component, including work by Mr Eaves himself.

As she appears in Star Trek Online, Sovereign doesn’t have saucer separation – but her MSD, made by Cryptic staffer Tim ‘Suricata’ Davies, does. Where does this leave the Archon?

Considering the Archon is the direct successor to the Sovereign-class, I assumed that the mission profiles of the two ships were largely the same. It doesn’t make much sense to produce a follow-on that is somehow less capable than the ship it is replacing, so even if it’s functionally not present within the game for balance or gameplay reasons, I opted to include the suggestion of saucer separation in the Archon’s MSD.

Having said that – a problem that I have almost constantly had with drawings of ships that have saucer separation is just how badly those separation lines cut into its key structures and decks. While an MSD is an abstracted 2D cross section of a ship that has a lot of beam – often combining sections that are far to the port and starboard of the centreline on to a single plate – separation planes are nonetheless difficult to visualise when their slopes visibly cut through areas of decks that are sometimes well over a hundred metres long. In including the separation plane on the Archon, I took care to ‘step it down’ as it moved forward – keeping the interlocks and separation mechanisms contained within their own compartments that, to the very best of my ability, did not needlessly cut into functional spaces around it.

I kept the ship’s battle bridge in the same relative position to that on the Sovereign class, just above and forward of the main navigational deflector, located several decks down below the top of the secondary hull section. An alternate position was considered within the ‘prow’ of the secondary hull, but that was instead – at the suggestion of a friend and collaborator – given over to an intelligence command centre which I will explain a little bit later in this write-up.

One fun aspect of the saucer separation capability is the ship’s main shuttlebay. It is horizontally bisected by the separation line. I imagine that during procedures to split the ship in two, the shuttle elevator platforms raise up to the flight deck and effectively seal as air locks with various locking pins clunking into place and buttoning up the section. Secondary doors might then expand either side of the lift shafts to provide the second seal for the engineering section, allowing the hydraulic lifts to pull back and stow themselves. It’s a very clean line which starts at the rear of the shuttlebay flight deck and extending forward, stepping down just before the primary ODN shaft, and again as it approaches the forward transporter rooms.

The very front of the secondary hull section forms a ‘dreadnought-style’ bow which slips away to become the ship’s new prow, and does so at a clean (almost vertical) angle that doesn’t unnecessarily intrude into the operational spaces in that section.

Shuttlebays:

The Archon’s got a major point of difference over the Sovereign-class, in that she only has the one large shuttlebay. (The ship’s fantail is a large secondary shuttlebay on the Sovereign, but is a fairly plainly detailed stump on the Archon with no visible doors.) On the face of it, I didn’t realise how much of a logistical challenge this presented in terms of space allocation for shuttles, fighters, and other craft. This meant that in order for the ship to really have enough shuttles (or what I consider to be enough, at least!) it really needed to have a fairly deep hangar hold. That brings the floor of the maintenance hangars down to the top of the ship’s warp core.

A through-deck hangar (much like the Galaxy and Akira class) was one possible alternative, but the shallower geometry of the Archon’s saucer section would mean that such an area would very severely reduce the number of useable compartments for things like science labs, transporter rooms, and crew quarters. The hangar and flight deck each occupy a height of two decks, and are – based on the position of the three launch bay doors at the rear of the saucer – wide enough to accomodate multiple small craft side by side. The entire saucer section, from bridge to saucer edge (which is also the lower-most deck with useable space) is only nine decks tall. It would be unusual, in my estimates, to dedicate close to fifty percent of the ship’s primary habitable area over shuttlebays.

The Archon does, however, actually have three other smaller shuttlebays elsewhere on the ship. One of these is rendered on the MSD and is located in the ventral section of the secondary hull, facing aft at the ‘divot’ rise of the keel. Two other, smaller bays are located on the ventral side of the saucer section (port and starboard) facing forward. These latter two shuttlebays are not rendered on the MSD, and would sit in an area close to where I’ve rendered stellar cartography and the primary ODN shaft. The downside of having several small shuttlebays rather than a couple of large ones is that it does limit the ship’s ability to fit larger types of shuttles onboard. Plus side: it meant I could back the secondary shuttlebay directly onto a cargo hold in the ship’s ventral hull, making for an excellent loading bay.

Engineering and Deflector:

As mentioned previously, the warp core of the Archon class seems to be situated well forward of where it was located on the Sovereign, running vertically just behind the main deflector. The three primary considerations on Main Engineering’s position would be the location of the warp core, the line of the main EPS conduit from the warp core intermix chamber to the nacelle pylons, and the physical size of the Main Engineering compartment itself. Having established the position of the warp core along the ship’s length, I cross-referenced it to the level of the nacelle pylons to get the position of the warp core’s reaction chamber.

That marks the centre of main engineering, around which the compartment could be build. This was looking to fall extremely close to the level of the main deflector spaces below, meaning the traditional layout of corridors that run across the ship in front of engineering couldn’t be done. Had the warp core been placed any higher, then the main EPS line would also not properly intersect with the ship’s pylons. The internal layout is likely to have the corridors running down either side of engineering, with turbolift access toward the stern. Of the compromises that could be made, this was probably the best solution I could come up with.

The Engineering compartment is a pretty standard size, being based on the dimensions of the Sovereign class. It sits on deck 17, directly above the deflector control systems. There is an upper Deflector Control room on deck 16 (hello, First Contact reference!) and a second control roo down just above the torpedo magazine, at deck 20.

Less ideal, but still mostly acceptable, the warp core does not have a clear ejection port on the dorsal hull and can only be ejected down through the ventral hull. Directly above the warp core is the lower maintenance deck of the shuttlebay hangars.

The main navigational deflector has a much wider aperture than the one on the Sovereign class, and its structure is closely based on the style of the Phalanx-class master systems display. It’s much less an abstract assembly of geometric shapes, and instead a slightly more detailed rendering of the actual structures, including their mounting spaces, cables, and frames.

I tried to preserve this ‘blocked out’ style across the MSD extensively, with the most obvious second example being the nacelle structure and areas surrounding the plasma injection control centre. I think it’s an effective look that draws the eye – which is helpful because the deflector and the systems around it sit at the very heart of the ship’s operations.

The first of three torpedo launchers sits directly beneath the deflector in an arrangement very similar to the ventral launchers of the Sovereign. Notably, the Archon class has fewer torpedo launchers than the Sovereign itself, with just six of them present in three mounts located here at the ventral fore, the ventral aft, and stern. By comparison, the Sovereign had either ten or eleven torpedo launchers by the end of Nemesis, depending on which analysis you believe.

Curiously, the two classes have an identical balance of torpedo firepower, biased heavily to the aft quarter. Of the Sovereign’s 10 (maybe 11) launchers, six of them face aft, while four of them face forward. It’s a similar story on the Archon, with four launchers facing aft and just two pointed forward. The Archon has no torpedo launchers under her saucer like Sovereign’s turret, though a smaller version of this turret (without a Captain’s yacht) is present on the ship’s fantail.

Considering the stated torpedo armament of these kinds of ships is usually quoted in the hundreds of rounds, I took care to ensure the magazines (complete with loaders) were reasonably large in size.

Intelligence & Assault

It’s written on the packet. The Archon is an Intelligence Assault Cruiser, and while I’ve never been especially sure of what an Assault Cruiser is (aside from a vessel perhaps designed to break through lines and wreak havoc at the centre of the enemy formation) the addition of Intelligence capabilities to the ship is an eyebrow-raiser. Accordingly, I gave the MSD several facilities that directly relate to that mission role.

The Archon’s ‘turret’ position under the saucer doesn’t have the same torpedo launchers that the Sovereign has, and that space is instead occupied by a large, ominous looking black trapezium of unknown function and design. Traditionally, this space on a starship has also been the location of a large sensor array (such as that on the Galaxy class, Excelsior, and even Constitution).

Instead of a standard planetary sensor dome, I chose to put a very large surveillance sensor that, of a particularly extensive and sophisticated type that might be used by Starfleet Intelligence. It pairs nicely with the fact the ship has a cloaking device, after all.

Directly above that sensor, and attached to it, is an Intelligence Operations Centre.

This room is basically one big command centre for members of Starfleet Intelligence to conduct surveillance, analysis, and covert operations deep within the ship. I even baffled the compartment with some cladding to give the spooks some privacy, and it separates the entire area from surrounding sections. The only areas around this command centre are library and research areas, along with a crew lounge and life support systems.

The second thing I thought to add was an area of the lower decks that was dedicated to an embarked MACO contingent or hazard team. MACO was – according to the conjectural opinion of Cryptic’s Thomas Marrone – reinstated in Star Trek Online and ‘wholly subsumed’ by the organisation as ‘marines’.

The MACO decks, spanning two levels just above the secondary shuttlebay and Cargo Bay 2, include all manner of facilities that the MACO might need. There is a shooting range, an armoury, quarters, a commander’s office (right next to his quarters), a briefing room, gymnasium, and basic lounge area. This all sits with the conjectural ‘armoured’ section of the ship, and yes – for the keen eyed out there – that is a bathroom with toilets in it. If there is one thing I am most pleased about in completing a Master Systems Display, it’s the fact this ship actually has a loo!

Finally on the intelligence front, there is a mission operations centre directly above the shuttle bay:

I laboured over this area for some time. It’s actually too short within the deck spacing to be a lounge, but it’s also very, very close to the flight deck’s traffic control centre which sits in the ‘bird nest’ that hangs from the flight deck roof. The idea of putting a crew lounge right near air traffic control didn’t seem like an overly smart idea, so the area was instead given over to an orbital mission operations centre, from which I imagine the ship’s security and tactical officers can work with MACO, Hazard Team, and other relevant parties to coordinate the landing of security forces on planetary surfaces. The big windows visible to the aft of the observation platform give excellent visibility toward space over the approaches of the shuttlebay, but – notably – they lack any windows or field of view in the direction of the shuttlebay approach, making it unsuitable for traffic control.

Warp Drive

Moving along swiftly, the warp nacelles are something I ended up being quite proud of. Nacelles are not typically something that are well detailed on Master Systems Displays, so I referred to a lot of cutaways and old Trek reference manuals to work out how they all go together. In the end, I fashioned something of a useable machinery space between the bussard collectors and the warp field coils where systems like plasma injectors, control rooms, and power lines could be placed. Of particular note was the Quantum Slipstream Drive envelopes which line each side of the Archon class’s nacelles.

There is very little in the way of canon about the QSD and how it works. Voyager never went into it in any detail, and that particular series often played fast and loose with its engineering treknobabble. It’s an open book, with only a few sets to refer to for inspiration. In Star Trek Online, Starfleet has been playing with QSD technology for over thirty years since the end of Voyager, so I asked the question: How much has it advanced? And what the heck does a Quantum Slipstream Drive coil look like in 2410?

Thankfully, we do have some idea. The USS Dauntless’s quantum slipstream drive in Voyager was a roughly circular node of devices that surrounded a central core fashioned out of what looked to be a plasma globe. If this was Starfleet’s starting point for inspiration, then that was something I could work with

The orientation of the QSD sleeves on either side of the nacelle makes for interesting internal arrangements. I tried a variety of designs including several ‘molecule model’ spheres chained together in a zig-zag patten. I tried more traditional Trek geometric constructions made out of multiple sized, clean-looking boxes, but none of this really fit within the loosely triangular shape of the sleeve.

In moments of silly frustration, I did look to less serious references. Enter Battlestar Galactica’s invocations of ‘spin up the FTL drive’, or the puppet General Hammond in Episode 200 of Stargate SG1 proclaiming, “I’m the General, and I want it to spin!”.

My mental acrobatics went from what train of thought to another, and before long I was indeed asking myself: “…does a QSD even spin?”

The answer was probably ‘no’, but nonetheless I found myself thinking more about rounded shapes – and that original circular pattern seen in Voyager aboard the Dauntless. I didn’t imagine the device would physically rotate, but it almost certainly had an electrical component that worked within the ‘spindles’ that we saw. Hmm… Spindles… spinning… electrical…

I don’t quite know when the word ‘spinnaker’ entered my mind, but a spinnaker on a sailing vessel is a large sail that is deployed for short periods to to drive the vessel down-wind. They aren’t always appropriate and are stowed when not necessary – which pretty much meets the description of a Quantum Slipstream Drive. It’s a name that stuck as I built it up. I am really, really happy with how it turned out. As an added bonus, it makes for some good bridge banter when the Captain wants the QSD deployed or retracted. I can quite easily imagine “Douse the Socks” being an order issued to bring a ship to impulse.

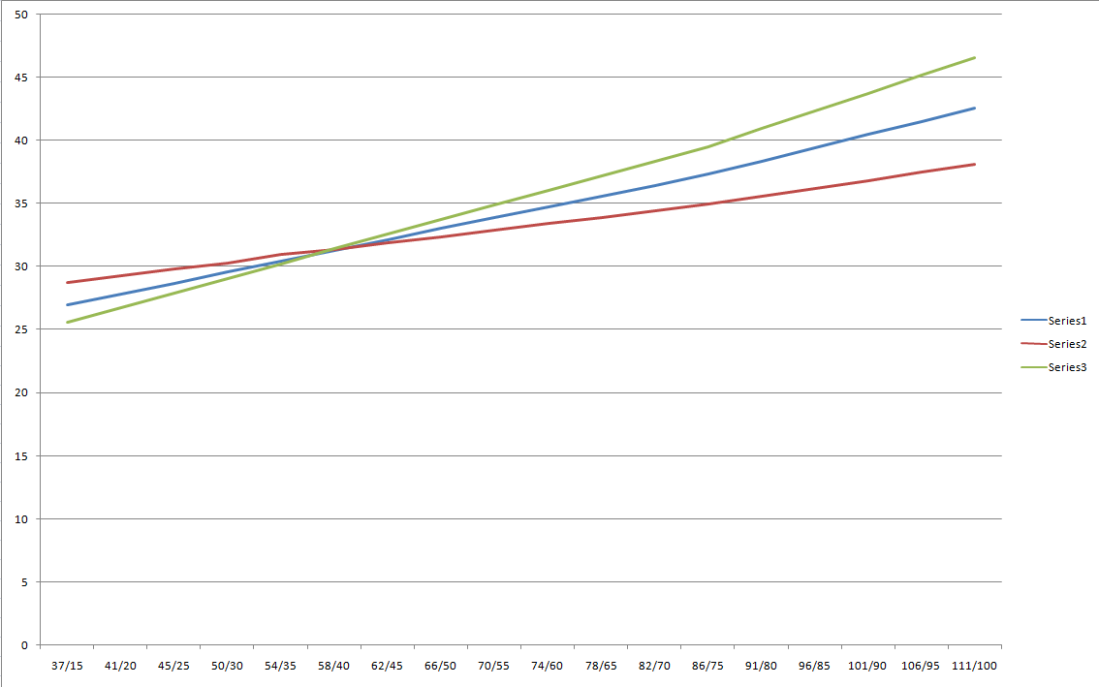

The nacelles themselves have fewer field coils than the Sovereign class (22 pairs vs the Sovereign’s 24) but they are much larger, being at times four or five times heavier towards the front of the engines. Considering just how well-endowed the ship’s nacelles are, I expected that making them balanced would be a reasonable challenge. In the end, they actually came out alright. One consideration is that the nacelles are cambered at an angle of about 30 degrees outboard, which makes them even longer than they appear in a side-orthographic. This is reflected more in the inset graphic I produced to show off the ship’s quantum slipstream envelope, with each blue line intersecting each point of the ship’s main QSD sleeves.

There are tonne of details buried all over the MSD. From the static ship model displays in the bridge conference room, to observation corridors at the forward lounge that overlook the ship’s inboard areas, to easter eggs and traceable wiring that leads from weapons arrays to small generators and fusion reactors, I tried to step up the level of detail that people generally see in an MSD. As this is my first attempt, I’m proud of the result, and hope you enjoy pouring over it to explore it in depth. Have any suggestions or feedback? Drop me a comment or an email. I’ve love to hear your thoughts.

Some final acknowledgements – I’d simply thank fleet mate @AdmLancel for his constant counsel and being a sounding board for what you see in the MSD, Cryptic’s Tim Davies for the inspiration provided by his own MSDs, Cryptic’s Thomas Marrone for his wonderful Jayces’ Interstellar series (and all its technical details that I relied on to make decisions for this project) and D.M. Phoenix who produced the Phalanx-class and its MSD which probably led me to do this project to begin with.

Cheers.

*Yes yes, I can see you back there, Constitution fans.